Second-order logic

In logic and mathematics second-order logic is an extension of first-order logic, which itself is an extension of propositional logic.[1] Second-order logic is in turn extended by higher-order logic and type theory.

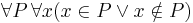

First-order logic uses only variables that range over individuals (elements of the domain of discourse); second-order logic has these variables as well as additional variables that range over sets of individuals. For example, the second-order sentence  says that for every set P of individuals and every individual x, either x is in P or it is not (this is the principle of bivalence). Second-order logic also includes variables quantifying over functions, and other variables as explained in the section Syntax below. Both first-order and second-order logic use the idea of a domain of discourse (often called simply the "domain" or the "universe"). The domain is a set of individual elements which can be quantified over.

says that for every set P of individuals and every individual x, either x is in P or it is not (this is the principle of bivalence). Second-order logic also includes variables quantifying over functions, and other variables as explained in the section Syntax below. Both first-order and second-order logic use the idea of a domain of discourse (often called simply the "domain" or the "universe"). The domain is a set of individual elements which can be quantified over.

Expressive power of second order logic

Second-order logic is more expressive than first-order logic. For example, if the domain is the set of all real numbers, one can assert in first-order logic the existence of an additive inverse of each real number by writing ∀x ∃y (x + y = 0) but one needs second-order logic to assert the least-upper-bound property for sets of real numbers, which states that every bounded, nonempty set of real numbers has a supremum. If the domain is the set of all real numbers, the following second-order sentence expresses the least upper bound property:

In second-order logic, it is possible to write formal sentences which say "the domain is finite" or "the domain is of countable cardinality." To say that the domain is finite, use the sentence that says that every surjective function from the domain to itself is injective. To say that the domain has countable cardinality, use the sentence that says that there is a bijection between every two infinite subsets of the domain. It follows from the upward Löwenheim–Skolem theorem that it is not possible to characterize finiteness or countability in first-order logic.

Syntax

The syntax of second-order logic tells which expressions are well formed formulas. In addition to the syntax of first-order logic, second-order logic includes many new sorts (sometimes called types) of variables. These are:

- A sort of variables that range over sets of individuals. If S is a variable of this sort and t is a first-order term then the expression t ∈ S (also written S(t) or St) is an atomic formula. Sets of individuals can also be viewed as unary relations on the domain.

- For each natural number k there is a sort of variable that ranges over all k-ary relations on the individuals. If R is such a k-ary relation variable and t1,..., tk are first-order terms then the expression R(t1,...,tk) is an atomic formula.

- For each natural number k there is a sort of variable that ranges over functions that take k elements of the domain and return a single element of the domain. If f is such a k-ary function symbol and t1,...,tk are first-order terms then the expression f(t1,...,tk) is a first-order term.

For each of the sorts of variable just defined, it is permissible to build up formulas by using universal and/or existential quantifiers. Thus there are many sorts of quantifiers, two for each sort of variable.

A sentence in second-order logic, as in first-order logic, is a well-formed formula with no free variables (of any sort).

In monadic second-order logic (MSOL), only variables for subsets of the domain are added. The second-order logic with all the sorts of variables just described is sometimes called full second-order logic to distinguish it from the monadic version.

Just as in first-order logic, second-order logic may include non-logical symbols in a particular second-order language. These are restricted, however, in that all terms that they form must be either first-order terms (which can be substituted for a first-order variable) or second-order terms (which can be substituted for a second-order variable of an appropriate sort).

Semantics

The semantics of second-order logic establish the meaning of each sentence. Unlike first-order logic, which has only one standard semantics, there are two different semantics that are commonly used for second-order logic: standard semantics and Henkin semantics. In each of these semantics, the interpretations of the first-order quantifiers and the logical connectives are the same as in first-order logic. Only the ranges of quantifiers over second-order variables differ in the two types of semantics.

In standard semantics, also called full semantics, the quantifiers range over all sets or functions of the appropriate sort. Thus once the domain of the first-order variables is established, the meaning of the remaining quantifiers is fixed. It is these semantics that give second-order logic its expressive power, and they will be assumed for the remainder of this article.

In Henkin semantics, each sort of second-order variable has a particular domain of its own to range over, which may be a proper subset of all sets or functions of that sort. Leon Henkin (1950) defined these semantics and proved that Gödel's completeness theorem and compactness theorem, which hold for first-order logic, carry over to second-order logic with Henkin semantics. This is because Henkin semantics are almost identical to many-sorted first-order semantics, where additional sorts of variables are added to simulate the new variables of second-order logic. Second-order logic with Henkin semantics is not more expressive than first-order logic. Henkin semantics are commonly used in the study of second-order arithmetic.

Deductive systems

A deductive system for a logic is a set of inference rules and logical axioms that determine which sequences of formulas constitute valid proofs. Several deductive systems can be used for second-order logic, although none can be complete for the standard semantics (see below). Each of these systems is sound, which means any sentence they can be used to prove is logically valid in the appropriate semantics.

The weakest deductive system that can be used consists of a standard deductive system for first-order logic (such as natural deduction) augmented with substitution rules for second-order terms.[2] This deductive system is commonly used in the study of second-order arithmetic.

The deductive systems considered by Shapiro (1991) and Henkin (1950) add to the augmented first-order deductive scheme both comprehension axioms and choice axioms. These axioms are sound for standard second-order semantics. They are sound for Henkin semantics if only Henkin models that satisfy the comprehension and choice axioms are considered.[3]

Why second-order logic is not reducible to first-order logic

One might attempt to reduce the second-order theory of the real numbers, with full second-order semantics, to the first-order theory in the following way. First expand the domain from the set of all real numbers to a two-sorted domain, with the second sort containing all sets of real numbers. Add a new binary predicate to the language: the membership relation. Then sentences that were second-order become first-order, with the formerly second-order quantifiers ranging over the second sort instead. This reduction can be attempted in a one-sorted theory by adding unary predicates that tell whether an element is a number or a set, and taking the domain to be the union of the set of real numbers and the power set of the real numbers.

But notice that the domain was asserted to include all sets of real numbers. That requirement cannot be reduced to a first-order sentence, as the Löwenheim-Skolem theorem shows. That theorem implies that there is some countably infinite subset of the real numbers, whose members we will call internal numbers, and some countably infinite collection of sets of internal numbers, whose members we will call "internal sets", such that the domain consisting of internal numbers and internal sets satisfies exactly the same first-order sentences satisfied as the domain of real-numbers-and-sets-of-real-numbers. In particular, it satisfies a sort of least-upper-bound axiom that says, in effect:

- Every nonempty internal set that has an internal upper bound has a least internal upper bound.

Countability of the set of all internal numbers (in conjunction with the fact that those form a densely ordered set) implies that that set does not satisfy the full least-upper-bound axiom. Countability of the set of all internal sets implies that it is not the set of all subsets of the set of all internal numbers (since Cantor's theorem implies that the set of all subsets of a countably infinite set is an uncountably infinite set). This construction is closely related to Skolem's paradox.

Thus the first-order theory of real numbers and sets of real numbers has many models, some of which are countable. The second-order theory of the real numbers has only one model, however. This follows from the classical theorem that there is only one Archimedean complete ordered field, along with the fact that all the axioms of an Archimedean complete ordered field are expressible in second-order logic. This shows that the second-order theory of the real numbers cannot be reduced to a first-order theory, in the sense that the second-order theory of the real numbers has only one model but the corresponding first-order theory has many models.

There are more extreme examples showing that second-order logic with standard semantics is more expressive than first-order logic. There is a finite second-order theory whose only model is the real numbers if the continuum hypothesis holds and which has no model if the continuum hypothesis does not hold. This theory consists of a finite theory characterizing the real numbers as a complete Archimedean ordered field plus an axiom saying that the domain is of the first uncountable cardinality. This example illustrates that the question of whether a sentence in second-order logic is consistent is extremely subtle.

Additional limitations of second order logic are described in the next section.

Second-order logic and metalogical results

It is a corollary of Gödel's incompleteness theorem that there is no deductive system (that is, no notion of provability) for second-order formulas that simultaneously satisfies these three desired attributes:[4]

- (Soundness) Every provable second-order sentence is universally valid, i.e., true in all domains under standard semantics.

- (Completeness) Every universally valid second-order formula, under standard semantics, is provable.

- (Effectiveness) There is a proof-checking algorithm that can correctly decide whether a given sequence of symbols is a valid proof or not.

This corollary is sometimes expressed by saying that second-order logic does not admit a complete proof theory. In this respect second-order logic with standard semantics differs from first-order logic; Quine (1970, pp. 90–91) pointed to the lack of a complete proof system as a reason for thinking of second-order logic as not logic, properly speaking.

As mentioned above, Henkin proved that the standard deductive system for first-order logic is sound, complete, and effective for second-order logic with Henkin semantics, and the deductive system with comprehension and choice principles is sound, complete, and effective for Henkin semantics using only models that satisfy these principles.

The history and disputed value of second-order logic

Predicate logic was primarily introduced to the mathematical community by C. S. Peirce, who coined the term second-order logic and whose notation is most similar to the modern form (Putnam 1982). However, today most students of logic are more familiar with the works of Frege, who actually published his work several years prior to Peirce but whose works remained in obscurity until Bertrand Russell and Alfred North Whitehead made them famous. Frege used different variables to distinguish quantification over objects from quantification over properties and sets; but he did not see himself as doing two different kinds of logic. After the discovery of Russell's paradox it was realized that something was wrong with his system. Eventually logicians found that restricting Frege's logic in various ways—to what is now called first-order logic—eliminated this problem: sets and properties cannot be quantified over in first-order-logic alone. The now-standard hierarchy of orders of logics dates from this time.

It was found that set theory could be formulated as an axiomatized system within the apparatus of first-order logic (at the cost of several kinds of completeness, but nothing so bad as Russell's paradox), and this was done (see Zermelo-Fraenkel set theory), as sets are vital for mathematics. Arithmetic, mereology, and a variety of other powerful logical theories could be formulated axiomatically without appeal to any more logical apparatus than first-order quantification, and this, along with Gödel and Skolem's adherence to first-order logic, led to a general decline in work in second (or any higher) order logic.

This rejection was actively advanced by some logicians, most notably W. V. Quine. Quine advanced the view that in predicate-language sentences like Fx the "x" is to be thought of as a variable or name denoting an object and hence can be quantified over, as in "For all things, it is the case that . . ." but the "F" is to be thought of as an abbreviation for an incomplete sentence, not the name of an object (not even of an abstract object like a property). For example, it might mean " . . . is a dog." But it makes no sense to think we can quantify over something like this. (Such a position is quite consistent with Frege's own arguments on the concept-object distinction). So to use a predicate as a variable is to have it occupy the place of a name which only individual variables should occupy. This reasoning has been rejected by Boolos.

In recent years second-order logic has made something of a recovery, buoyed by George Boolos' interpretation of second-order quantification as plural quantification over the same domain of objects as first-order quantification (Boolos 1984) Boolos furthermore points to the claimed nonfirstorderizability of sentences such as "Some critics admire only each other" and "Some of Fianchetto's men went into the warehouse unaccompanied by anyone else" which he argues can only be expressed by the full force of second-order quantification. However, generalized quantification and partially-ordered, or branching, quantification may suffice to express a certain class of purportedly nonfirstorderizable sentences as well and it does not appeal to second-order quantification.

Applications to complexity

The expressive power of various forms of second-order logic on finite structures is intimately tied to computational complexity theory. The field of descriptive complexity studies which computational complexity classes can be characterized by the power of the logic needed to express languages (sets of finite strings) in them. In particular, if we consider second-order logic over finite structures:

- NP is the set of languages expressible by existential, second-order logic (Fagin's theorem, 1974).

- co-NP is the set of languages expressible by universal, second-order logic.

- PH is the set of languages expressible by second-order logic.

- PSPACE is the set of languages expressible by second-order logic with an added transitive closure operator.

- EXPTIME is the set of languages expressible by second-order logic with an added least fixed point operator.

Relationships among these classes directly impact the relative expressiveness of the logics over finite structures; for example, if PH=PSPACE, then adding a transitive closure operator to second-order logic would not make it any more expressive over finite structures.

Power of the existential fragment

The existential fragment (EMSO) of monadic second-order logic (MSO) is second-order logic without universal second-order quantifiers, and without negative occurrences of existential second-order quantifiers. Over (possibly infinite) words w ∈ Σ*, every MSO formula can be converted into a deterministic finite state machine. This again can be converted into an EMSO formula. Thus EMSO and MSO are equivalent over words. For trees as input, this result holds as well. However, over the finite grid Σ++, this property does not hold any more, since the languages recognized by tiling systems are not closed under complement. Since a universal quantifier is equivalent to a negated existential quantifier, which cannot be expressed, alternations of universal and existential quantifiers generate bigger and bigger classes of languages over Σ++.

See also

- Second-order propositional logic

Notes

- ↑ Shapiro (1991) and Hinman (2005) give complete introductions to the subject, with full definitions.

- ↑ Such a system is used without comment by Hinman (2005).

- ↑ These are the models originally studied by Henkin (1950).

- ↑ The proof of this corollary is that a sound, complete, and effective deduction system for standard semantics could be used to produce a recursively enumerable completion of Peano arithmetic, which Gödel's theorem shows cannot exist.

References

- Andrews, Peter (2002). An Introduction to Mathematical Logic and Type Theory: To Truth Through Proof (2nd ed.). Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- Boolos, George (1984). "To Be Is To Be a Value of a Variable (or to Be Some Values of Some Variables)". Journal of Philosophy 81: 430–50.. Reprinted in Boolos, Logic, Logic and Logic, 1998.

- Henkin, L. (1950). "Completeness in the theory of types". Journal of Symbolic Logic 15 (2): 81–91. doi:10.2307/2266967. http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0022-4812%28195006%2915%3A2%3C81%3ACITTOT%3E2.0.CO%3B2-I.

- Hinman, P. (2005). Fundamentals of Mathematical Logic. A K Peters. ISBN 1-56881-262-0.

- Putnam, Hilary (1982). "Peirce the Logician". Historia Mathematica 9: 290–301.. Reprinted in Putnam, Hilary (1990), Realism with a Human Face, Harvard University Press, pp. 252–260.

- W.V. Quine (1970). Philosophy of Logic. Prentice-Hall.

- Rossberg, M. (2004). "First-Order Logic, Second-Order Logic, and Completeness". In V. Hendricks et al., eds.. First-order logic revisited. Berlin: Logos-Verlag. http://homepages.uconn.edu/~mar08022/papers/RossbergCompleteness.pdf.

- Shapiro, S. (2000). Foundations without Foundationalism: A Case for Second-order Logic. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-825029-0.

- Vaananen, J. (2001). "Second-Order Logic and Foundations of Mathematics". Bulletin of Symbolic Logic 7 (4): 504–520. doi:10.2307/2687796. http://www.math.ucla.edu/~asl/bsl/0704/0704-003.ps.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

![\forall A \Big[\Big(\exists w (w \in A) \land \exists z\,\forall w ( w \in A \rightarrow w \leq z)\Big) \rightarrow \exists x\,\forall y \Big([\forall w (w \in A \rightarrow w \leq y)] \leftrightarrow x \leq y\Big)\Big].](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/831ed7af9d4ca1467d0e01c0b2e4f90f.png)